Tools themselves are the interfaces between the LLMs and APIs; they take in machine-generated structured outputs to then trigger some action that produces an output, whether it’s requested information or confirmation of an action. These tools then really represent the bridge between APIs and LLMs. So the way that they're written is important to how well an agent uses them, which influences an agents capability or usefulness.

This article is just a few thoughts on writing tools that agents can use to achieve their goals. Usability, specifically Cognitive Ergonomics, is a key term that should be top of mind when writing tools. In this case, the UX of tools is really for the LLMs/agents.

In the physical realm, a good tool communicates its use; it provides surfaces and symbols that allow the external viewer, at first glance, to interpret its use. A tool should show you how to use it, and it should provide feedback when it doesn’t work.

Model Context Protocol

MCP represents a standardization effort that creates a common interface between agents and external services. When users need to connect their own agents / client apps to services like GitHub, Slack, Blender, or Shopify, MCP provides a straightforward path without requiring custom builds. This standardization creates a plug-and-play ecosystem that's particularly valuable for extending agent capabilities beyond your core application or spooling up an agent quickly.

There is a powerful and growing ecosystem of open-source MCP servers that can be leveraged quickly and easily. While it remains off-the-shelf, the capabilities offered by MCP servers will continue to grow, especially as providers continue to refine and improve them. It serves as a large ecosystem of tools that can be used out of the box to interact with APIs or services.

They function as "off-the-rack" solutions, which means it’s not tailored specifically for your application: you give up control over implementation, error handling approaches, and response formatting.

It also commodifies agent capabilities, meaning anything your MCP agent can do, it’s doing the same thing anywhere else that it’s been implemented. In other words, you won’t exceed common capabilities with publicly available tools; they’re effectively fungible commodities. Custom tooling can be a moat - the way it remembers and recalls, any of its unique capabilities, overall reliability etc. will all be influenced by the approach to your agents tooling.

Custom Tools

A bespoke approach ensures that tools return exactly the information your agent needs in the format it expects, with no unnecessary detail, minimizing context window bloat while delivering to the agent what it expects. Custom-built tools require upfront development, but they provide precise control over every aspect of agent-API interaction. They can be optimized for your specific data structures, error cases, and user workflows, and messaging can be tightly managed for user experience or self-healing and error correction.

Finding a Balance

When evaluating whether to use existing toolkits, consider factors like how central the functionality is to your application, how specialized your requirements are, and how broad you want them to be. Novel or unique capabilities typically benefit from custom implementation, while standardized integrations with third-party services are often well-served by MCP.

Whether defined through the model context protocol, or custom defined functions, tools exist on a gradient of controllability, each with their own reliability and usability tradeoffs:

Code Execution

At one end of the gradient are tools that primarily execute code, like Blender MCP which essentially offers a single "execute Blender code" function. This approach provides maximum flexibility but requires the agent to write custom code for each operation, essentially programming on the fly.

While powerful, this approach can introduce reliability issues since the agent is expected to generate syntactically correct code reliably. This is effectively asking the agent to both build the tool, and use it to complete its primary goal. When errors occur during execution, the agent must interpret them and attempt to fix its generated code, increasing the probability of failure loops.

Hybrid

In the middle are hybrid approaches that offer simple input fields but still require some custom code for operations like data queries or table creation. These provide some structure while allowing customization for specific needs.

Hybrid tools offer more guidance than pure code execution but can still face reliability issues when custom code snippets contain errors or don't account for edge cases in the underlying API.

Simplified Function-Based Approach

At the other end of the spectrum are fully digested tools that represent discrete actions as simple verb-based functions with clear parameters. For example, rather than requiring an agent to write code to search the web, a search_web(query) function handles all the complexity internally.

In this case, code is already written and tested, and the agent only has to invoke the tool and provide a few simple parameters.

This approach constrains the agent to well-defined operations. Functions with limited, simplified inputs are easier for agents to use correctly because they represent a clear set of possible actions with specific parameter requirements.

The reliability of an agent is heavily influenced by how its tools are implemented. Code generation approaches, are powerful and adaptable, but can also increase risks. Function-based approaches trade flexibility for improved reliability. A combination of both covers most use cases while allowing the agent to write code to execute what the prebuilt tools don’t offer.

When flexibility is needed, consider providing specialized functions for common operations and escape hatches for edge cases, rather than defaulting to code generation for everything.

Building Agent-Friendly Toolkits & MCP Servers

Whether you’re building a custom function-based toolkit for yourself, an MCP server for yourself, or ones for others to use, there are a few principles I try to keep in mind when building tools that might help in developing your own toolkit or MCP server.

Cognitive Ergonomics

Cognitive ergonomics examines how information, tasks, and interfaces align with the mental processes of their users. When the “user” is language model, the same principles still apply, just reframed for a synthetic cognition.

A cognitively ergonomic tool surfaces only the context that the model needs to reason effectively (clear affordances, logical parameter names, concise docstrings) while suppressing extraneous noise that would bloat its context window or tempt it into hallucinating. Inputs should be unambiguous, mutually exclusive when possible, and accompanied by schema‑level hints that implicitly steer the model toward valid ranges, lowering its cognitive load and reducing error rates.

Outputs should follow a stable, predictable structure so the agent can parse them, with explicit success and failure messages that eliminate ambiguity. By shaping the tools this way, toolmakers create an environment where the agent’s limited attention budget is spent on high‑level planning rather than focusing on syntax, meaning convergence on correct actions and more reliable performance end‑to‑end.

Principle: Surface only the information the model truly needs; every extra token is a stray cognitive load and an invitation to hallucinate.

Abstraction of Complexity

Effective tools abstract underlying complexity from agents. For example, I have a MacOS agent toolkit that abstracts AppleScript syntax into actions that the agent can take. Rather than requiring agents to understand and constantly rewrite AppleScript syntax, these tools create a simplified interface that hides the implementation details.

This abstraction allows agents to focus on their goals rather than the mechanics of achieving them. It also helps prime the model in terms of what focused actions it can take, they’re suggestive of what it might have to do. The tools handle the translation between high-level intentions ("create a reminder") and the complex sequence of AppleScript commands needed to accomplish that task, creating a clean separation of concerns.

Its pre-built functions abstract away the need to write AppleScript for every task, allowing agents to operate with simple verb-object commands like create_note(title, content) or search_notes(query).

While these prebuilt tools largely cover the majority of requirements, the abstractions won’t cover all use-cases. The toolkit provides a direct terminal interface that allows agents to write custom AppleScript when a request is outside the scope of its pre-built functions.

While abstraction enhances efficiency for common tasks, flexibility is still essential for handling edge cases and specialized requirements. By offering both structured tools and flexible alternatives, it achieves a balance: simplicity for routine operations and flexibility when needed, all while maintaining an interaction model that agents can easily understand.

Principle: Hide the plumbing to let agents reason in high‑level intents while the tool translates those intents into low‑level commands.

Clear Docstring Guidance

Clear, well‑structured docstrings are the agent’s first window into how a tool should be used, so they must act like a miniature contract: a concise description of the tool’s purpose, an explicit Args section that lists each parameter and its expected type and possibly examples, and a Returns section that spells out what will come back (and in what structure). In Orchestra we don’t burden every tool with full JSON schema metadata, so this args list inside the docstring does the heavy lifting: it primes the model with valid inputs, prevents guessing at parameter names, and reduces false starts before the tool is ever invoked. By clarifying intent, inputs, and outputs up front, a good docstring cuts token waste, minimizes error‑handling detours, and lets the agent focus its reasoning on accomplishing the user’s goal rather than deciphering an opaque interface.

Focused Return Statements

Return statements should be minimal, focused on the key update/action/change (successfully sent email to {recipient}) and any context that's relevant to a followup (urls, confirmation IDs). When an agent receives a response from a tool, it needs to quickly understand what happened and what information might be needed next. Verbose responses with unnecessary details can confuse the agent or lead it down the wrong path of recovery.

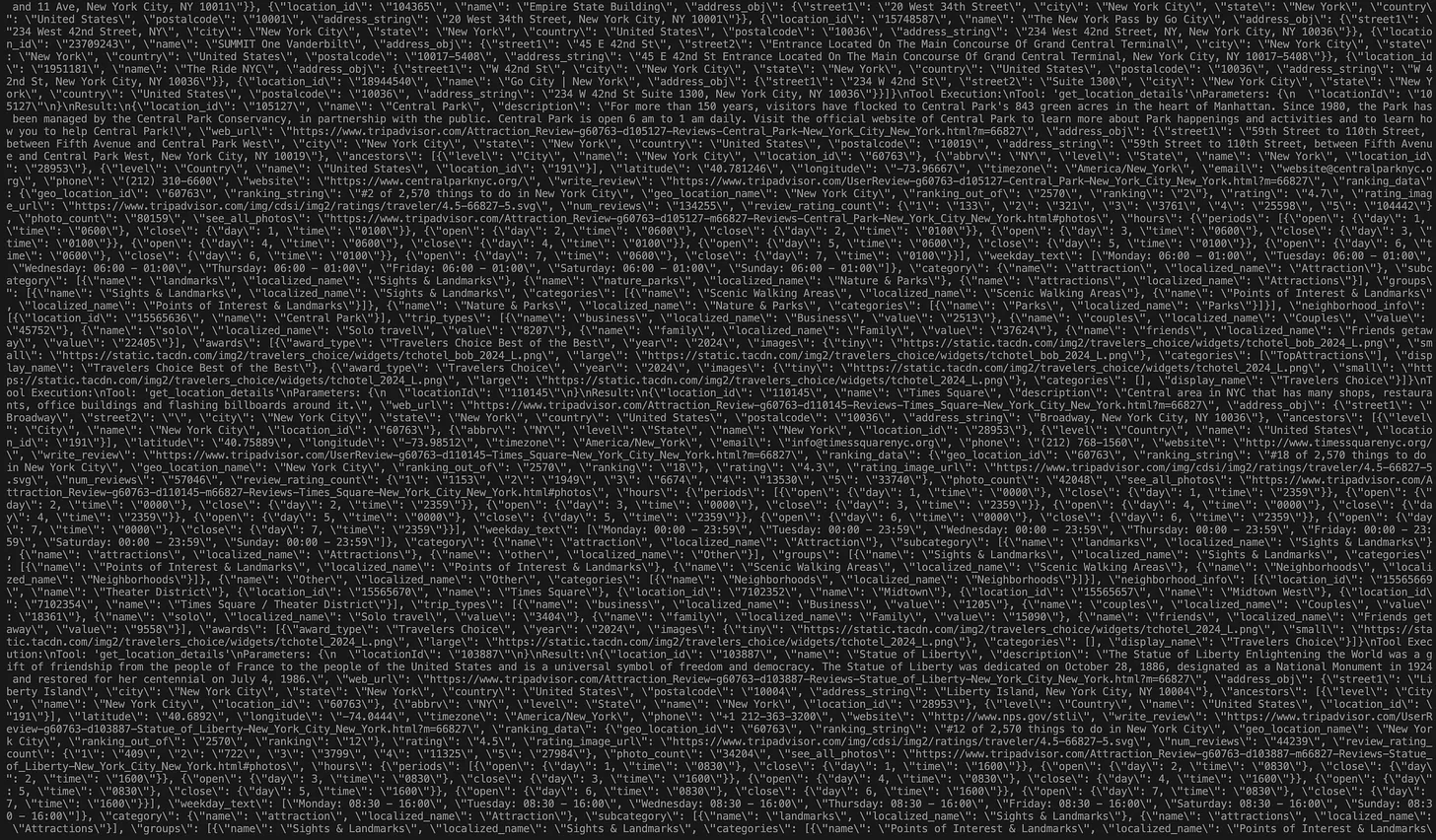

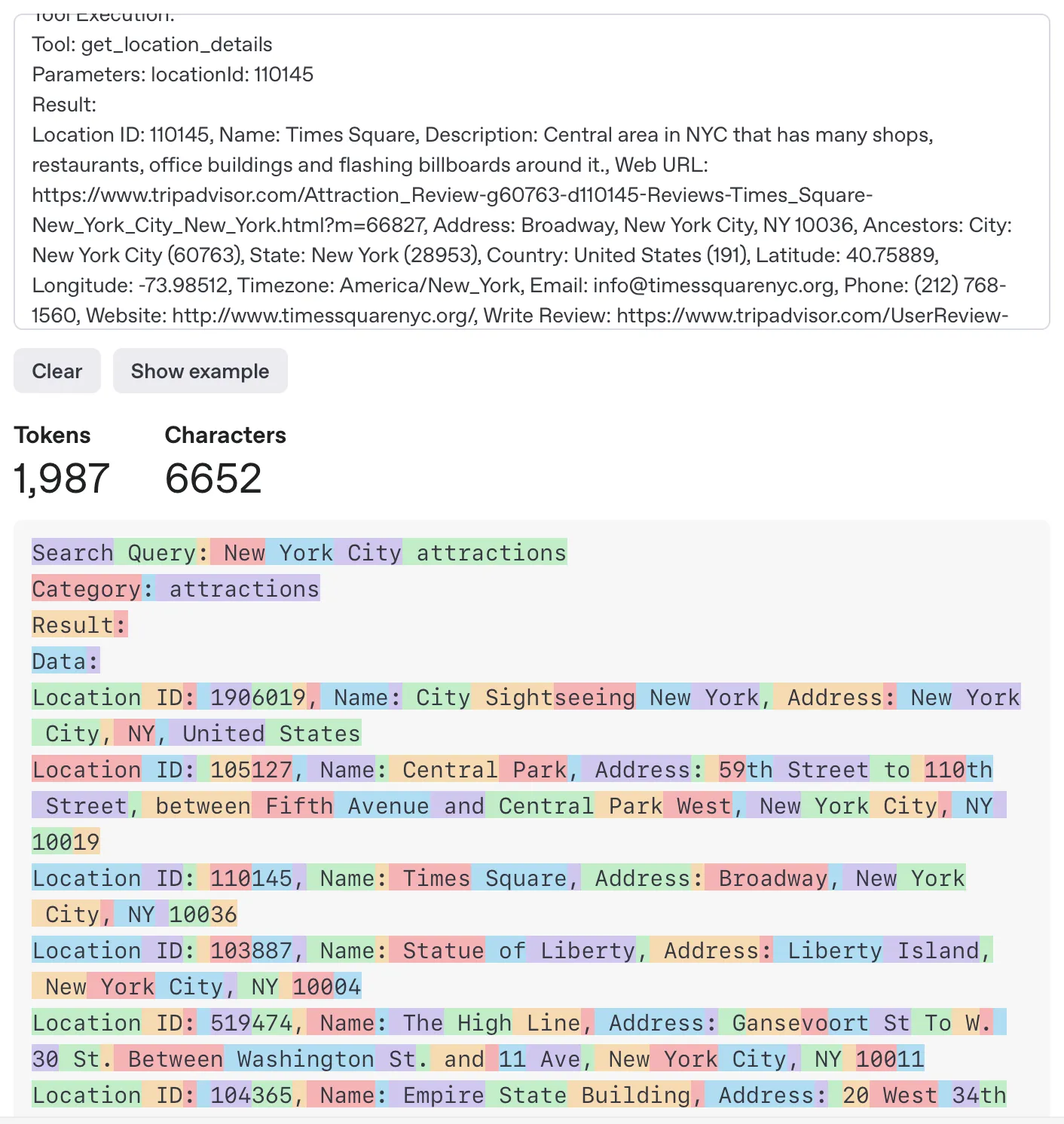

In this instance below, a search query from a public Tripadvisor MCP returned information with a tremendous amount of formatting characters. These can help to structure and separate elements, but in this case it’s totally unprocessed, bloating the context window, increasing costs unnecessarily, and reducing the cognitive ergonomics of the returned data and the tool itself.

This single tool call returned 5,400 tokens, but these results can be simplified and destructured, which would reduce token count to about 2,000, without losing useful information.

Some requests return a ton of data for other reasons, but for agents taking action, helpers can reformat a large return statement into a focused one, forwarding back to the agent only the information relevant to the action taken. It’s also an opportunity to convert JSON to YAML for token count reduction. This reduces cost in the token inputs but also limits context window bloat and lets the agent focus on the relevant tokens without all of the formatting and escape characters.

Principle: Emit tight, task‑oriented responses; if the agent doesn’t need to reference a field, it probably shouldn’t be in the payload.

Effective Error Handling

For a tool to be what some call "self-healing", in that the agent can recover after incorrect attempts, you need to catch input errors and provide messages to help the agent correct, or even suggest that it stop trying if it gets a specific type of error, and raise the issue to the user.

If an API key is missing, for instance, the tool could return a message like "API key missing. Stop trying and ask the user to provide a valid API key" rather than just returning an error code. These messages help guide the agent to the next action in each error case.

You don't have to be too prescriptive because agents can interpret errors themselves, but if you find an agent is getting stuck or lost in a series of actions with a toolkit, you can examine error handling and how you're returning that context to the agent.

Principle: Treat errors as conversation turns—return messages that tell the agent what went wrong and how to recover (or when to escalate).

Set, Communicate, and Enforce Limits

For example, when handling historical financial data, a request to something like Yahoo finance for financial history information can return a tremendous amount of data when requesting 6 months of price data at a one minute interval. These types of requests can fill a context window pretty easily. So we can use interval checks to ensure that the returned data isn’t overwhelming, and return a message saying “requested interval of {interval} is too fine over that long of a timespan ({timespan}), please reduce interval or time span”. The docstring / tool description should guide agents to avoid even calling for too much data in the first place by informing them of the limitations to the inputs before it calls the tool. This sets the agent up to use the tool correctly, but also handles context-overflow avoidance and self-correction if it does make the mistake of requesting too much data.

Principle: Design guardrails that prevent context overflow by establishing clear boundaries on data volume, communicating these limits upfront, and enforcing them with actionable feedback when exceeded.

Success Responses & Next Steps

Success responses should be clear and focused, returning any context that's important for potential follow-up actions. Some tools like a basic math calculator can just return the answer, but something like a click_webpage function could not just click an element but also wait and fetch the HTML content or screenshot of the following page so the agent has context about what happened as a result of the click.

Principle: Return not just confirmations but the context needed for follow-up actions, anticipating the agent's next reasoning step rather than forcing it to seek additional information.

Observability

Build observability into tools from the start with decorators or logging that capture method calls, parameters, and results. This helps with debugging, usage analytics, and understanding how tools are being used in production.

Ideal Defaults

You have a few options for an API input parameter. Hide it totally from the agent by hardcoding the parameter, create an optional input that would override the default, or make it a required parameter the agent must determine each time. A well designed tool takes an API endpoint and abstracts away the unnecessary details and sets up the agent for the ideal interaction model by setting inputs as required, optional, or abstracted away. The agent sees the default and it can bias the agent toward it, so you want to set defaults that are logical but overridable.

Principle: Design tools with sensible defaults for common use cases, but allow for customization through optional parameters. Support both simple and advanced usage patterns.

Putting It All Together

When designing tools for agents, think of yourself as creating an interface that another intelligence will use. The clearer and more intuitive your tool's inputs and outputs are, the more effectively the agent can leverage it.

Remember that agents, unlike humans, don't have common sense or contextual understanding beyond what they've been trained on. They rely heavily on the explicit information your tool provides. A well-designed tool anticipates the user’s needs, provides just the right amount of information, and guides the user toward successful outcomes. In our case, the user is an agent and the tool software..

In the end, good tool design for agents follows many of the same principles as good tool design for humans: clear affordances and focused functionality, but with the unique considerations that come from having an agent as your user. Cognitive ergonomics becomes a major consideration in this world of building agent capabilities.